Testing the State of an Object

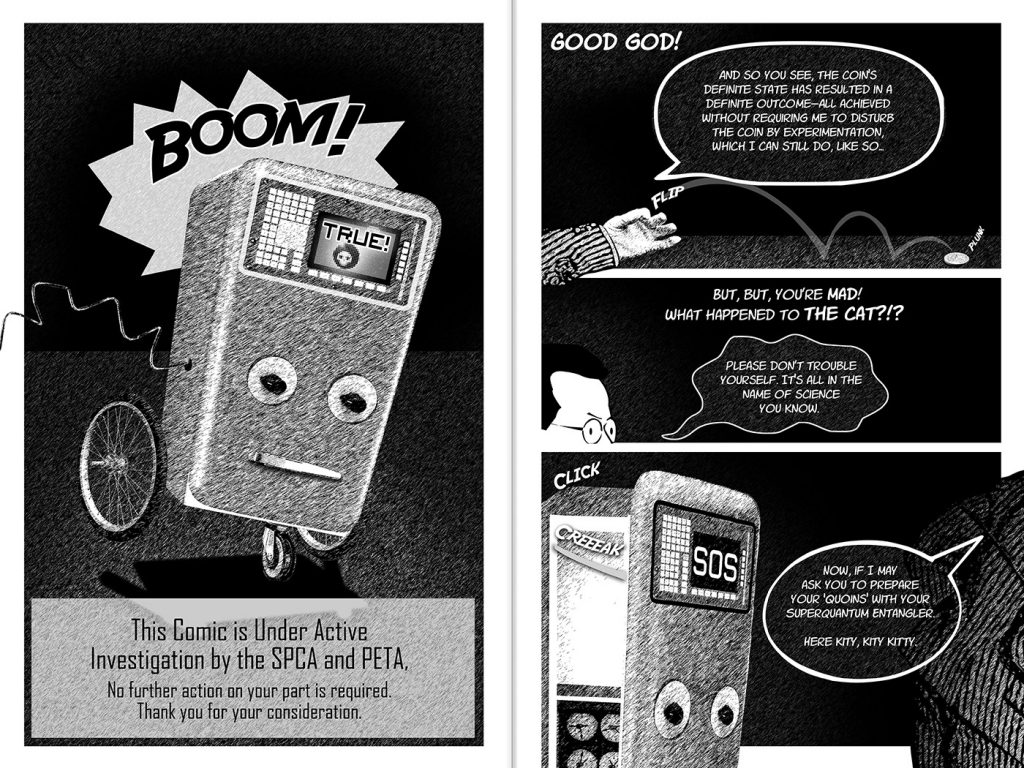

Our commonsense intuition tells us that all physical objects have a state, a catalog of determinate properties, even if we don't know what those properties are. This, however, is not the case for entangled quantum particles. If we try to assign a specific state to each of the particles in an entangled pair, we inevitably get a contradiction. Schrödinger used a dead/alive cat to illustrate the absurdity of a world in which physical objects must exist in an ambivalent state of reality.

Totally Random casts Schrödinger as a mad scientist with a device designed to read the state of any physical object, such that it can deem true or false any testable statement about it. See what happens when the device is hooked up to a pair of entangled quoins that simply cannot have a definite state!

Schrödinger and Einstein

Schrödinger introduced his famous cat in a side comment as a “ridiculous case” in an article “The present situation in quantum mechanics”. Here’s how he put it:

One can even set up quite ridiculous cases. A cat is penned up in a steel chamber, along with the following diabolical device (which must be secure against direct interference by the cat): in a Geiger counter there is a tiny amount of radioactive substance, so small, that perhaps in the course of one hour one of the atoms decays, but also, with equal probability, perhaps none; if it happens, the counter tube discharges and through a relay releases a hammer which shatters a small flask of hydrocyanic acid. If one has left this entire system to itself for an hour, one would say that the cat still lives if meanwhile no atom has decayed. The first atomic decay would have poisoned it. The ψ-function of the entire system would express this by having in it the living and the dead cat (pardon the expression) mixed or smeared out in equal parts.

As Schrödinger goes on to say, the point of the cat is to show that “an indeterminacy originally restricted to the atomic domain becomes transformed into macroscopic indeterminacy, which can then be resolved by direct observation.” This shows that quantum mechanics doen't represent reality by a “blurred model”, like a cloud or a bank of fog. The fact that you can resolve the indeterminacy or indefiniteness by opening the steel chamber and looking, says Schrödinger, shows that the quantum description is like the sort of description provided by “a shaky or out-of-focus photograph” where some information is lost, in other words an incomplete description of something quite definite.

In a supportive letter to Schrödinger dated December 22, 1950, Einstein commented (after inexplicably modifying the device to blow up the cat instead of poisoning it):

You are the only contemporary physicist, besides Laue, who sees that one cannot get around the assumption of reality—if only one is honest. Most of them simply do not see what sort of risky game they are playing with reality—reality as something independent of what is experimentally established. They somehow believe that the quantum theory provides a description of reality, and even a complete description; this interpretation is, however, refuted, most elegantly by your system of radioactive atom + Geiger counter + amplifier + charge of gunpowder + cat in a box, in which the ψ-function of the system contains the cat both alive and blown to bits. Is the state of the cat to be created only when a physicist investigates the situation at some definite time? Nobody really doubts that the presence or absence of the cat is something independent of the act of observation. But then the description by means of the ψ-function is certainly incomplete, and there must be a more complete description. If one wants to consider the quantum theory as final (in principle), then one must believe that a more complete description would be useless because there would be no laws for it. If that were so then physics could only claim the interest of shopkeepers and engineers; the whole thing would be a wretched bungle.

Schrödinger and Einstein

Einstein and Schrödinger thought that something should be added to the theory that resolves the indefiniteness at the quantum level. It’s the indefiniteness that’s the problem here, not the indeterminism of quantum mechanics.

Einstein had an extensive correspondence with Max Born. Wolfgang Pauli thought that Born persistently misunderstood Einstein’s position on quantum mechanics. At one point, Pauli intervened to set Born straight in a letter dated March 31, 1954:

Also, Einstein gave me your manuscript to read; he was not at all annoyed with you, but only said you were a person who will not listen. This agrees with the impression I have formed myself insofar as I was unable to recognise Einstein whenever you talked about him in either your letter or your manuscript. It seemed to me as if you had erected some dummy Einstein for yourself, which you then knocked down with great pomp. In particular, Einstein does not consider the concept of “determinism” to be as fundamental as it is frequently held to be (as he told me emphatically many times), and he denied energetically that he had ever put up a postulate such as (your letter, para. 3): “the sequence of such conditions must also be objective and real, that is, automatic, machine-like, deterministic.” In the same way, he disputes that he uses as criterion for the admissibility of a theory the question: “Is it rigorously deterministic?”

Einstein’s point of departure is “realistic” rather than “deterministic,” which means that his philosophical prejudice is a different one.

You might be surprised at Pauli’s clarification of Einstein’s position, in the light of Einstein’s often-quoted comment about God not playing dice. In a letter to Born dated December 4, 1926, Einstein wrote:

Quantum mechanics is certainly imposing. But an inner voice tells me that it is not yet the real thing. The theory says a lot, but does not bring us any closer to the secret of the “old one.” I, at any rate, am convinced that He is not playing dice.

Einstein didn’t believe that quantum mechanics was “the real thing.” But his critique of the theory, as in the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen argument, doesn’t depend on assuming determinism, but rather on what Pauli identifies as a “realistic prejudice”. In Totally Random terms, that would be the assumption that a quoin has a definite taste before being peeled, or that there are some quoin variables with definite values that define a "being-thus", as Einstein put it, a catalog of properties amounting to an “instruction set” for a quoin to land “heads” or “tails” when tossed heads up or tails up.

You can find Einstein's letter to Schrödinger in Letters on Wave Mechanics on p. 39, Einstein's letter to Born about God not playing dice in The Born-Einstein Letters on p. 91, and Pauli's letter to Born in the same book on p. 221.